Water Rights: The 'Hidden' Asset in North Texas Land Deals

![[HERO] Water Rights: The 'Hidden' Asset in North Texas Land Deals](https://cdn.marblism.com/KGNea1zMHep.webp)

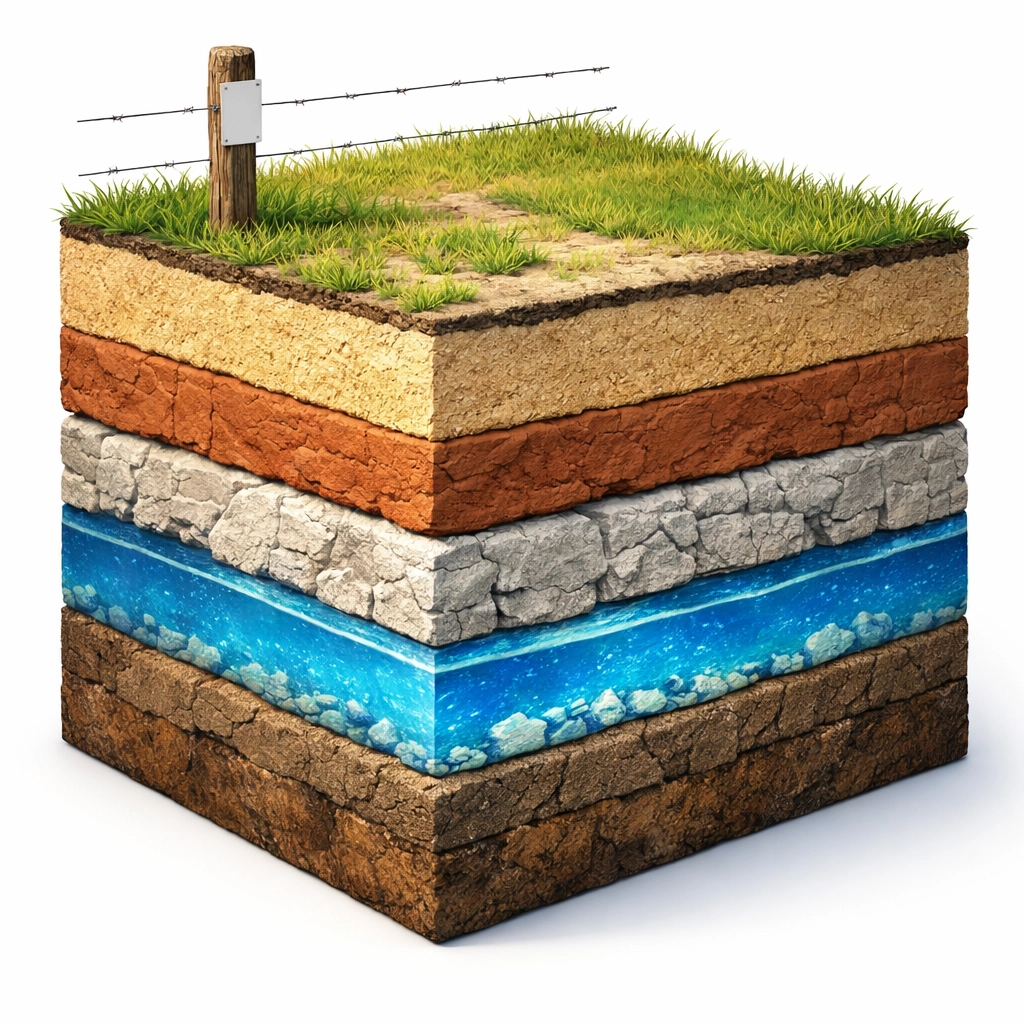

When buyers look at a 50-acre tract in Grayson County or a development site in Denton, they see the frontage, the zoning, and the location. What they don't always see, and what can kill a deal faster than bad access, is what's underneath and what's available for delivery: water.

In 2026, water rights and well capacity aren't just footnotes in the due diligence packet. They're the "make or break" line items that determine whether that rural land becomes a subdivision, stays a pasture, or sits in legal limbo for years.

The North Texas Water Reality

North Texas doesn't have the luxury of local rivers feeding every county. We're not sitting on the Colorado River or pulling from the Great Lakes. The Dallas-Fort Worth region relies on a network of surface water reservoirs, think Lake Lewisville, Lake Ray Hubbard, and Lake Texoma, and a massive system of long-distance water pipelines managed by entities like the North Texas Municipal Water District (NTMWD).

That system covers approximately 2,200 square miles, maintains over 600 miles of water pipelines, and manages more than 250 sites across eleven counties. It's a marvel of infrastructure, but it also means one thing for developers: if you're not in the service area, you're in a different league of complexity.

The result? Properties with established water access and utility service capacity command real premiums, while those dependent on uncertain or unavailable water sources face significant constraints, and significant discounts.

Why 2026 is Different

For years, the conversation around rural development focused on roads, zoning, and proximity to growth. Water was something people assumed they'd figure out later. But in 2026, that assumption is costing people deals.

Here's what changed:

Increased scrutiny on rural development. Counties and municipalities are requiring more detailed water plans before approving plats or issuing permits. The days of drilling a well and hoping for the best are fading fast, especially in areas with groundwater conservation districts.

Capacity constraints. As North Texas continues to explode, the existing water infrastructure is being stretched. New developments aren't just plugging into unlimited capacity, they're often waiting in line or negotiating extensions that add months (or years) to the timeline.

Climate reality. Droughts aren't hypothetical anymore. The 2022 and 2023 water restrictions reminded everyone that surface water isn't infinite, and groundwater management is getting tighter.

If you're buying land with the intent to develop it, water needs to be at the top of your checklist, not buried in paragraph 12 of the engineer's report.

Water Certificates: The Permit to Build

In many North Texas counties, especially those under groundwater conservation districts like the North Trinity Groundwater Conservation District, you can't just drill a well and start pulling water. You need a water production permit or certificate, essentially, permission from the district to extract a specific amount of groundwater.

These certificates come with limits. You might be allowed to pull 25 acre-feet per year, or 50, or 100, depending on the size of your tract, the intended use, and the district's rules. If your development plan requires more water than your certificate allows, you've got a problem.

And here's the kicker: getting a certificate isn't automatic. The district evaluates factors like aquifer levels, existing usage in the area, and long-term sustainability. If the aquifer is already stressed, they might deny your application or significantly limit your allocation.

For a developer planning a 200-lot subdivision, that's not a minor detail. It's the whole ballgame.

Well Capacity: The Physical Limitation

Even if you have the legal right to pump water, that doesn't mean the well can deliver it. Well capacity: the actual volume of water a well can produce per minute or per day: depends on the geology underneath your property.

Some areas of North Texas sit on robust aquifers with high-yield wells that can support significant development. Others sit on thin layers of groundwater that barely support a single-family home, let alone a commercial project.

This is where the "invisible infrastructure" problem becomes painfully real. You can't see the aquifer. You can't see the rock formations or the recharge zones. You're essentially drilling blind until you hit water: and even then, you don't know if it's enough until you test the flow rate.

I've seen deals where buyers assumed a 100-acre tract could support a small subdivision, only to find out after drilling that the well produces less than 10 gallons per minute. That's barely enough for a few homes, let alone the 40 lots they had planned.

The Invisible Infrastructure Problem

When people think about infrastructure, they picture roads, power lines, and sewer systems. But water is the invisible piece that holds it all together: and it's often the most expensive to fix when it's missing.

If you're buying land outside a municipal utility district (MUD) or a city's water service area, you're likely looking at one of three scenarios:

Private wells. You drill your own wells and hope they produce enough water to support your development. This is the cheapest option upfront but the riskiest long-term.

Water extensions. You negotiate with a nearby utility to extend water lines to your property. This can cost hundreds of thousands: or millions: of dollars, depending on the distance and the utility's willingness to extend service.

Package plants and community systems. You build your own water treatment system to serve the development. This requires permits, ongoing maintenance, and a level of regulatory compliance that most small developers aren't equipped to handle.

None of these options are simple. And none of them are cheap. That's why properties with existing water access trade at such a premium compared to those without it.

The Impact on Land Values

Let's talk numbers. Properties within existing utility service boundaries: especially those with confirmed water capacity: consistently outperform properties that don't have those features. We're not talking about a 5% or 10% difference. In some cases, the gap is 30% to 50% or more, depending on the market and the development potential.

A 20-acre tract in Anna with city water access might trade for $15,000 to $20,000 per acre. A comparable tract five miles outside the city limits, with no water and no immediate path to get it, might struggle to break $10,000 per acre: even if the zoning and location are similar.

Why? Because the buyer is absorbing all the risk and all the cost of solving the water problem. And in 2026, that's a big ask.

Conversely, properties with water challenges may trade at discounts, but resolving those issues requires navigating complex regulatory and infrastructure requirements that extend approval timelines and add substantial compliance costs. For institutional buyers: like national homebuilders or large-scale developers: that uncertainty is often enough to walk away from a deal entirely.

Due Diligence: The Water Checklist

If you're serious about buying land for development in North Texas, here's what needs to be on your due diligence checklist before you ever make an offer:

Check the water service area. Is the property within a municipal water district or city service area? If so, does the utility have capacity to serve your project, or are you looking at a years-long wait for infrastructure upgrades?

Understand groundwater rules. Is the property located in a groundwater conservation district? If so, what are the permitting requirements, and are there any restrictions on well usage?

Test well capacity. If the property relies on private wells, get a professional hydrogeologist to assess the aquifer and estimate potential yield. Don't rely on the neighbor's well as a proxy: aquifer conditions can vary dramatically over short distances.

Factor in extension costs. If water isn't available on-site, get a preliminary estimate for extending service. Talk to the utility directly and ask about their extension policies, cost-sharing programs, and timelines.

Review historical water data. Has the area experienced well failures or aquifer depletion? Are there any ongoing disputes over water rights or usage?

These aren't small details. They're the foundation of whether your project pencils out.

The Bottom Line

Water rights and well capacity are the hidden assets: and hidden liabilities: in North Texas land deals. In a market where everyone is focused on location, zoning, and highway access, the guys who win are the ones who understand that none of that matters if you can't deliver water to the site.

Properties with established water access are trading at premiums because they eliminate a massive layer of risk and cost. Properties without water aren't worthless, but they require a much deeper level of due diligence and a much longer development timeline.

If you're looking at rural land for development: or even a long-term hold with the expectation that someone else will develop it later: water needs to be one of your first questions, not your last.

At Cooper Land Company, we've been helping buyers and sellers navigate these exact issues for years. We know which tracts have water, which ones don't, and what it takes to solve the problem when it's missing. If you're evaluating a deal and need someone who understands the invisible infrastructure, let's talk.

OUR LISTINGS